The best way that I can sum up the experience of reading Nona the Ninth is (and I say as much below in this interview) like watching Captain America: The Winter Soldier and sitting on your hands screaming at Cap to realize that it’s Bucky!!! beneath the mask. Every memorable line in Tamsyn Muir’s The Locked Tomb series is embedded in layers of context, like skeletons buried just below the surface of the Ninth House. So even though we don’t know who Nona is at the start of the third novel (despite having a bevy of theories), it quickly becomes apparent that we know her world and that we recognize the people she loves, even if they’re known by different names.

And yet—part of the fun of Nona is experiencing moments and characters completely devoid of context. Like this interview: I could tell you, with no further explanation, such delightful phrases from Muir as “this book has a serious case of gender”; “a psychosexual mess of roleplaying and bad meals”; “a ten thousand year old James Bond MILF with attachment issues.” But it’s even better when you know what questions—and which necromancers, cavaliers, Lyctors, Edenites, or all of the above—these answers apply to! Come for the hamburger T-shirt and dog-invited birthday party, stay for talk of found families, resurrection versus rebirth, and enticing fodder for Alecto the Ninth fan theories.

I can also tell you that this interview will hit different both before and after you read Nona. For now, you can proceed without fearing getting spoiled (the only vague ones we’ve warned you about in their own section about midway through), but you’ll want to come back after you finish the book and give this another read. Because Muir is performing some bone magic, except with words—everything has two meanings depending on where you’re looking from.

***

Natalie Zutter: So I thought you were just being cheeky when you described Nona’s back copy as “How do you cope when the biggest jerk in the universe… turns out to be your secret crush’s out-of-town cousin?!?!,” but you completely delivered! How do you stay on top of such deliberate teases that pay off after people have read the book?

Tamsyn Muir: Honestly, the teases are easy—they’re just stuff I found funny or tickled me (or my editor) during the novel. OR they are total non sequiturs that don’t appear—I still get people asking pathetically about dog prom (mainly… my editor). I have a terrible love for saying things out loud in interviews or otherwise that people don’t notice until it is way too late, or putting things in that people’s eyes skim over. I am a walking Agent Arthur book.

NZ: Nona utilizes one of my favorite storytelling tropes, in which the narrator doesn’t know who various characters actually are, but the reader does—in this case, mostly through the use of aliases or formal titles, but with physical descriptions and/or context clues that amp up the dramatic irony until the big reveal. Reading the book was very akin to watching Captain America: The Winter Soldier, when you’re desperately waiting for Cap to recognize Bucky. How intentional was this? Was it fun to play with?

TM: It’s totally intentional! I’m wonderfully glad when it is fun and sad if it is infuriating, but at the end of the day I can only cater to myself. Nona is a walking dramatic irony generator. At this point I could let myself relax and trust that people were familiar enough with the world that they could enjoy it while I tied a blindfold around the POV—and also have the fun of getting to experience that world from a totally different vantage point. That’s why the Dramatis Personae is mostly dogs, code names, and Camilla.

Buy the Book

Nona the Ninth

NZ: This book has the least amount of bone magic of the series, but it’s not entirely absent. What made you decide to tell the story from the perspective of a character who can read not just body language, but literal movements of bone and skin?

TM: Oh, it’s so hard to not spoiler here. It is something essential about the character that I wanted to seed in. On a more meta level it was good and fun after writing Harrow, who is deeply paranoid and whose readings of people are either sort of faceblind—her understanding of non-Ninth mores is very poor—or worst possible interpretation. There’s body-language reading in Harrow with the Lyctors, who do it because they have ten thousand years of being in each other’s orbits: Nona’s is much more primal.

NZ: Gideon and Harrow heartbreakingly explore and interrogate the fraught power dynamics of the necromancer/cavalier relationship, but Nona brings together a bunch of loose keys, as it were—disparate necromancers and cavaliers severed from their other halves (or, in the case of Camilla and Palamedes, separated by a few seconds of consciousness). What was it like placing these characters together into found families or across the Blood of Eden interrogation table?

TM: Often I hate the phrase ‘found families’, because at its most yuk and saccharine it is an idealized friendship that caters to our most pathetic instincts—What If Someone Else Loved You Unconditionally Without Baggage About Your Shared Grandma And You Didn’t Have To Work Hard At It Ever—but the truth is that at its most beautiful, it is about unexpected commonality. Pyrrha would not have chosen to live with the Sixth House (she would’ve understood the Second a lot better and been able to manipulate them to her will more easily). Pyrrha is a ten thousand year old James Bond MILF with attachment issues, newly released from soul prison, who is forced to hang out with two intensely codependent, moral, ambitious nerds. She questions a hell of a lot about things they think they know everything about—and they question her on how comfortable she is in her cynicism. It’s a very strange household. And they are a found family, but I don’t think it’s a spoiler to say that in the last movement of the book Nona questions what that even means—their motives, what they all truly wanted out of each other, their pretenses: are they a family, or are they all just a psychosexual mess of roleplaying and bad meals? (The answer is yes.)

Of course, a psychosexual mess of roleplaying and bad meals can be beatified by love. That’s the part I had fun with—what love, in its purest and most messed-up forms, looks like between these people. In a way Camilla, Palamedes, Pyrrha and Nona are love’s dress rehearsal for the last book. You have not begun to see the horrors of love.

NZ: Death and resurrection are the life cycle of the Locked Tomb series, but Nona takes things in a slightly different but parallel direction by dealing with rebirth: Nona is slowly figuring out whoever she actually is, but she is also six months old and does things that babies do, like kissing her own reflection and telling everyone that she loves them. What differences have you found in writing about rebirth versus resurrection in your universe?

TM: Oh, that’s a fun differential! Especially because although Nona’s rebirth is a focus here, so is Camilla and Palamedes’ (now seen in their ‘two Sixths, one Cam’ incarnation) and Pyrrha’s (ten thousand years’ jail in her best friend). A question that Nona posits is, will these people choose rebirth—are they going to pick something new? Because resurrection, genuine resurrection, is the true second chance to pick up what you had before and keep going: rebirth is the new and unknown. Neither is necessarily better than the other, and indeed this series is about bad rebirths as well as good resurrections.

But Nona herself is having a lot of fun with rebirth. She doesn’t have to be weirded out by it in the way that Camilla and Palamedes are weirded out by her—she’s determined to ride this gravy train all the way into gravy station, where the dogs are.

WARNING: The next two questions are vaguely spoilery for Nona

NZ: In varying ways, Pyrrha, Camilla-and-Palamedes, and a certain Lyctor in leather pants all fuck around with gender, with their pronouns shifting based on whose eyes are looking out from the body. Was this something you always anticipated with certain cases of Lyctorhood (slash other forms of soul-sharing), or did it happen in the writing?

TM: My early readers have told me that this book has a serious case of gender. I think ALL the books have a serious case of gender; I consider my lesbianism to have a serious case of gender, and I’m not alone in… the lesbianism of gender (these words have stopped having meaning as I type them). I’m quite private about my personal experiences ’cos my friends and loved ones know my contexts but I don’t feel the need to be public about them and I hate being pushed into having to share stuff. Everyone hates when I’m pushed into sharing stuff, it ends up just being me bloviating on and at the end we’re all embarrassed.

But Lyctorhood from first blush has been a huge genderfuck as I understood it, and of course I got to understand it intimately from the get-go because I made it. Pyrrha uses gender like a nightstick. (Pyrrha uses most things like a nightstick.) Camilla-and-Palamedes both have a very strong sense of self and gender as Camilla, as Palamedes, while at the same time Camilla-and-Palamedes is a clusterfuck. Gender is kind of a weird buffet in the Locked Tomb universe as it is. Pronouns often exist independent of gender identities—there’s one character in particular who lives with bestowed pronouns and who is violently proud of them while at the same time quite likes experiencing what other pronouns mean. Titles are important for different people for different reasons. The choices people have made—or haven’t made—as to what their names are, what they’re called, are meant to be significant.

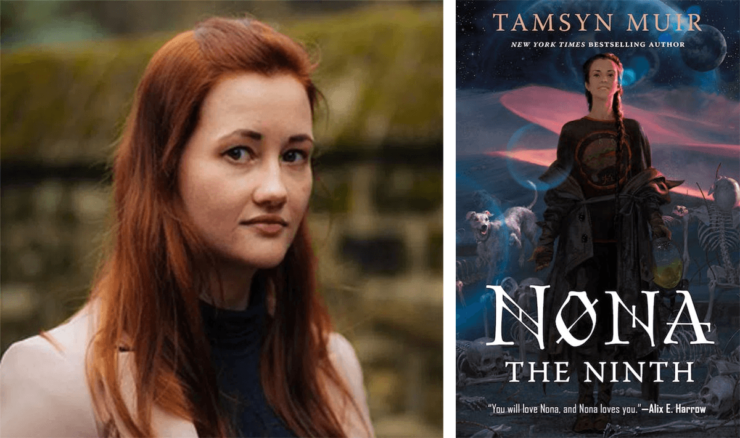

NZ: You really lean into the religious imagery with this book, from Nona’s Virgin Mary-esque pose on the cover to the John interludes, where he explains what happened a myriad ago to a certain someone. Was this intended as any sort of riff on the Biblical tale of Jesus in the desert with the devil for forty days, a.k.a. the Temptation of Christ? Or should we be looking more at the Healing of the Pool, which two of the interludes reference—will that play into Alecto and the conclusion of the Locked Tomb series?

TM: Yes.

Okay, to be less of an ass—much like gender, the Biblical imagery in this one comes out the closet. Readers will end up STICKY and GREASY with GENDER and BIBLE (that makes my book sound a lot more heavy-hitting than it is; it’s a book about comedy t-shirts). In a way this book retreads the Christ mythos explicitly—but when you’re mortal, when you acknowledge you’re calling the disciples and you’re referencing Bethesda, is it even a metaphor any more?? (Yes! But also no!) Biblical interludes in The Locked Tomb are achronological—they’re also complicated by having, like, six Christs. Check under your chair. Everyone gets a Christ. But then again—has it all been set up more or less inadvertently to mimic a Christian narratological pathway? Lyctorhood itself is a deeply screwy Dream of the Rood (Dream of the Rude? Note to self: do something with that).

I’ve already pretty much revealed that Alecto begins with the descent of Christ into Hades. So I can safely say that Alecto continues this line of questioning, except Alecto also posits, how many formal outfits can I stick the cast in and what colour.

***

OK, back to the broader questions:

NZ: Once you decided to make Nona into its own novel, did anything about the story change?

TM: No, alas. I’ve been forced to confront the fact that everything I wanted to do with Act One of Alecto, i.e. what became Nona, was its own novel. If I’d left it in Alecto you would have just been reading a novel where Act One was its own novel (so you could novel while you novel, etc).

NZ: Was any of the behavior in the settlement (wearing masks, eyeing one another suspiciously for symptoms of a disease, etc) inspired by the last few years of the pandemic?

TM: It became horribly prescient. I’d actually planned it out before the pandemic hit, but once the pandemic hit it took on a hideous new form that hit quite hard. I was like, ‘Ohh, this takes on… disreputable new meanings.’ In a way I’m quite lucky because I feel like readers will bring a hell of a lot of their own experiences to that table.

NZ: You mentioned during the Nona cover reveal that you wrote a 30k “divergence” for Gideon and Harrow while drafting Nona—is this an AU, and will we ever get to see it?

TM: Ha! I loved writing that AU—it was ace! Problem is that it is entirely its own story and is probably more like 50k if I bothered to write out the end. (I wrote to a specific part.) I wouldn’t want it out there before Alecto, is the thing. I’d just whack it up on AO3 except I think that would be, as the kids call it, cringe. Like a grandparent who arrives at your stripper party with their own weird, coughing stripper. I’m sorry because it has characters I really like who don’t make it into the Locked Tomb at all—Ram and Capris Asht, Colum Asht’s awful brothers; Modesty Even and Jessejon Threen; and Valentine the Ninth, whom the whole thing is named for. Then again, so much of it is epistolary from Gideon Nav’s POV you are better off not getting it because she is an appalling letter writer.

NZ: Soooo I only just learned that Alecto is the name of one of the Furies in ancient Greek mythology. Do tell!!

TM: Alecto, Ἀληκτώ—we don’t actually know what this Ancient Greek means but it’s most likely something to do with ‘the unspoken one’/‘the unspeakable one’; Robert Graves calls her ‘the unnamable’, which isn’t fact but is a good Graves one (Robert Graves has very much infiltrated this entire novel: there’s a huge reference that’s really me amusing myself because even Classicists are like when they hear it, ‘oh, that’s GRAVES though’). It can also mean ‘the unceasing—ceaseless—implacable’.

There were three Furies—Megaera and Tisiphone as Alecto’s sisters, and culturally we’re most familiar with their appearance in the Oresteia, in which they hunt down Orestes for the murder of his mother Klytaimnestra.

Certainly John does not like to name her, which is why her name is such a big deal in Harrow the Ninth.

NZ: Any hints as to the general vibe of the Alecto cover?

TM: It’s Tommy Arnold, so: 1. It’s beautiful!! 2. It’s very scary!!! 3. THAT (redacted) IS OPEN AS HELL!!!

NZ: In a LARB interview where you mentioned disconnecting from social media/the Internet during the beginning of the pandemic, you said that about all that was left to you was GeoCities shrines to people’s Neopets. What kinds of Neopets would different members of the Nine Houses foster? What about Nona?

TM: Nona would be creeped out by Neopets. Nona would be creeped out by the Chia. The skeletal structure of the Chia is uncertain. She would have far better understood the days when the Brucie pet was literally Bruce Forsyth. The Kiko makes her uncomfortable.

Don’t ask me to list more Neopets, I’m already showing my age. I still have my Webkinz duck, Googles. Any more of this and I will just start to exhale puffs of dust like a mummy.

NZ: OK, since you’re game to tease, one final (again, dancing on the edge of spoilery) question. This book has allowed us to spend so much time getting to know other characters from the first two books, but I can’t let this interview end without asking about our favorite Ninth House misfits: What can you say about where Harrow is at by the end of Nona slash start of Alecto? What about Gideon—body, soul, either/or, all of the above? Tease away!

TM: Harrowhark is in Hell.

Via “As Yet Unsent” and some hints in Nona, we know a lot more about where Gideon’s body is and what it has been doing (if you believe Coronabeth Tridentarius, providing some entries for her spank bank, but I would not necessarily believe Corona on this or anything else). The state of Gideon’s soul (and Harrow’s) are questions for Nona and Alecto. Remember that if Gideon’s soul is a Happy Meal, Harrow only ever ate the cheeseburger; whither the fries, the soda, and the tie-in toy?

You didn’t ask, but I like to think that Teacher is finally in the IHOP.

Nona the Ninth is available September 13th from Tordotcom Publishing

Read an excerpt here

Natalie Zutter sobbed her way through the final pages of Nona and cannot stop cackling over the Happy Meal metaphor for Lyctorhood. Come scream about The Locked Tomb with her over Twitter!

This does hit different before and after reading NONA.

I’m all the way in love with something not mentioned in any reviews or interviews about The Locked Tomb series and ESPECIALLY NONA—

ALL THAT REVOLUTIONARY GIRL UTENA STUFF!

Like, a character sheathing a sword in her own body, the way Anthy, the Rose Bride in UTENA, is a sheath for the Sword of Dio!

I didn’t know how much I needed a good UTENA fix until I read NONA.

@NZ: Thank you for this interview! It was a good ramp-down, having just finished devouring Nona the (Ninth?) just a few minutes ago.

@Tamsyn Muir: Thank you for this beautiful, broken universe! You are such an amazing and fun storyteller, and this is exactly the world I have needed to explore (and these are the characters I have needed to snicker and grieve and celebrate with) in this particular phase of my own beautiful, broken existence.

Much love,

mm